SPACE SHUTTLE FLIGHT RULE A2-62 ET FOOTPRINT CRITERIA

DESIGN MECO CONDITIONS AND ABORT MODE BOUNDARIES MUST PROVIDE AN ET IMPACT POINT (IP) FOOTPRINT, INCLUDING 3-SIGMA DISPERSIONS, WHICH SATISFIES THE FOLLOWING CONSTRAINTS:

A. NOMINAL MECO TARGET: THE ET IP FOOTPRINT IS MAINTAINED AT A MINIMUM OF 200 NM FROM ALL FOREIGN LAND MASSES (EXCEPT THE FRENCH-HELD POLYNESIAN ISLANDS, WHERE THE MINIMUM CLEARANCE MAY BE REDUCED TO 60 NM WHEN DICTATED BY MISSION OBJECTIVES) AND 25 NM FROM THE PERMANENT ICE SHELF. ALSO, THE ET IP FOOTPRINT MUST BE MAINTAINED AT LEAST 25 NM FROM U.S. ISLANDS.

Some days you protect the free world, some days you just protect the bird sanctuary.

I was recently reminded of our work in keeping the world safe from falling External Tanks as another, current, organization grapples with upper stage disposal.

The Space Shuttle system was completely reusable with one exception: the External Tank. Conceived to be analogous to the fuel drop tanks used by military aircraft, it was expended every mission. The ET was designed to be both as inexpensive and light weight. In its Super Light Weight configuration, it weighed 58,000 lbs. empty but could contain half a million gallons (735 tons) of cryogenic liquid hydrogen and oxygen in two separate tanks. An intertank structure in-between housed a steel I-beam that held the entire flight vehicle together: the reusable Orbiter holding the crew and the twin Solid Rocket Boosters.

Theoretically capable of taking the ET all the way into orbit, some ambitious engineers envisioned making a space station out of empty ETs. Maybe a topic for another blog post in the future. But the biggest problem with the ET was how to get rid of it safely so that no one could be hurt by it falling back to earth. The ET was jettisoned at nearly orbital velocity and traveled more than half way around the globe to reenter in a ‘broad ocean area’ where it would break up at around 250,000 feet altitude (45 nautical miles, or 75 kilometers high). The very thin wall aluminum and foam insulation vaporizing in the heat, many large pieces would still make it down to the ocean surface: the steel SRB I-beam, the 17-inch diameter LOX and LH2 separation valves, the sturdy structural attach points, and many more pieces.

A key aspect of this story is the requirement, by tradition, treaty, and standard practice, is that a sovereign nation generally considers the waters withing 200 n. mi. of its shore to be its area of economic and military interest (their Exclusive Economic Zone – EEZ). So, we were constrained to keep the pieces outside of 200 n. mi. from a foreign ‘land mass’ or in this case, an island. For US territory we could come to 25 n. mi. from the beach, much closer.

While the Orbiter used the smaller OMS engines to raise its orbit, the ET was on a ballistic path to destruction. Early in the program this was a two-burn sequence (aka ‘standard insertion’) resulting in the ET falling into the Indian Ocean. Later on, to get more performance out of the ET, the cutoff was changed slightly faster so that the Orbiter only needing one OMS engine thrust (aka ‘direct insertion’) to get to orbit while the ET splashed down in the Pacific Ocean. Direct insertion (DI) was a way to get more payload weight to a higher orbit.

Many times, NASA aircraft or other resources observed – at a distance – the breakup of the External tanks. The films of the reentry breakups were spectacular.

For reference you can watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1fkeTULQAps

Careful analysis of these videos led to a well-documented ‘debris catalog’ which was used in analytical computer programs to predict how far the parts might scatter. This pattern was the so called 3-sigma debris footprint. 3-sigma because it statistically encompassed 99.74% of all possible scattering of the parts. Analytically the footprint was almost 1,400 n. mi. long by 30 n. mi. wide (2,500 km by 55 km.)

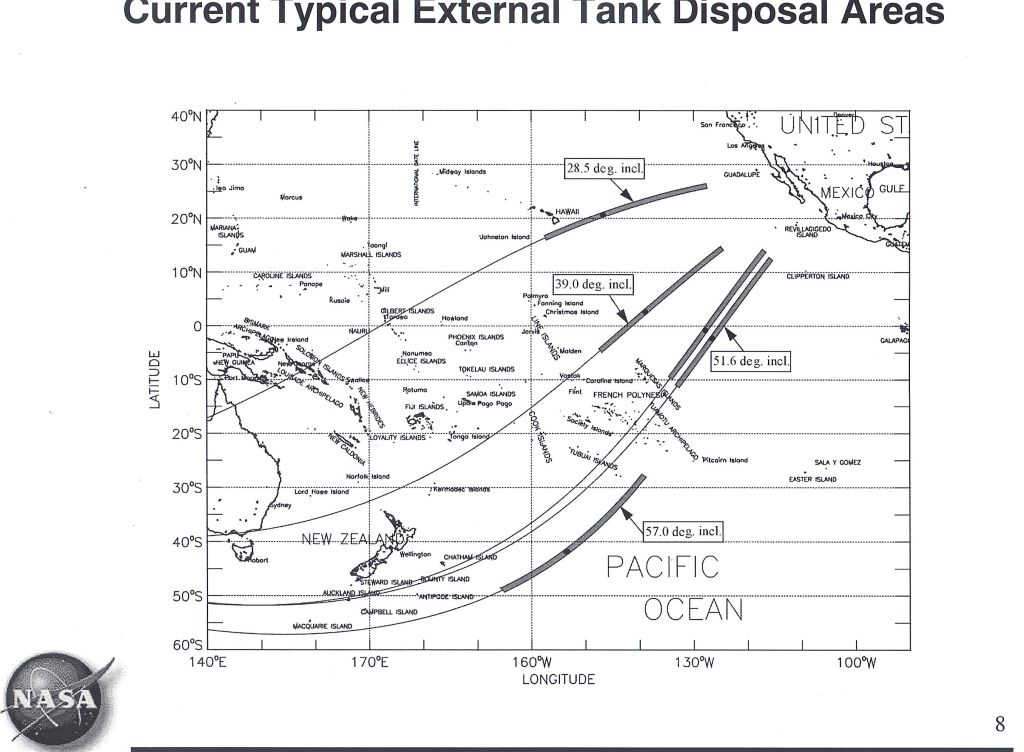

Of course, the planned inclination of the orbit, and a variable launch window for rendezvous flights (for ISS assembly) caused different swatches of the Pacific Ocean to be under the footprint.

We always planned very carefully where the ET would go and issued international Notices to Air Men and Notices to Mariners about the location and time when pieces might fall.

I was the Ascent Flight Director for one mission where the ET re-entered very near Hawaii just after local sunset. The spectacular breakup was observed by many on the Big Island and (according to what I heard) resulted in a call from the Governor of Hawaii to the NASA Administrator to find out ‘why is NASA bombing our state?’ Perhaps an apocryphal story, but why check? A good story is better than the truth some times.

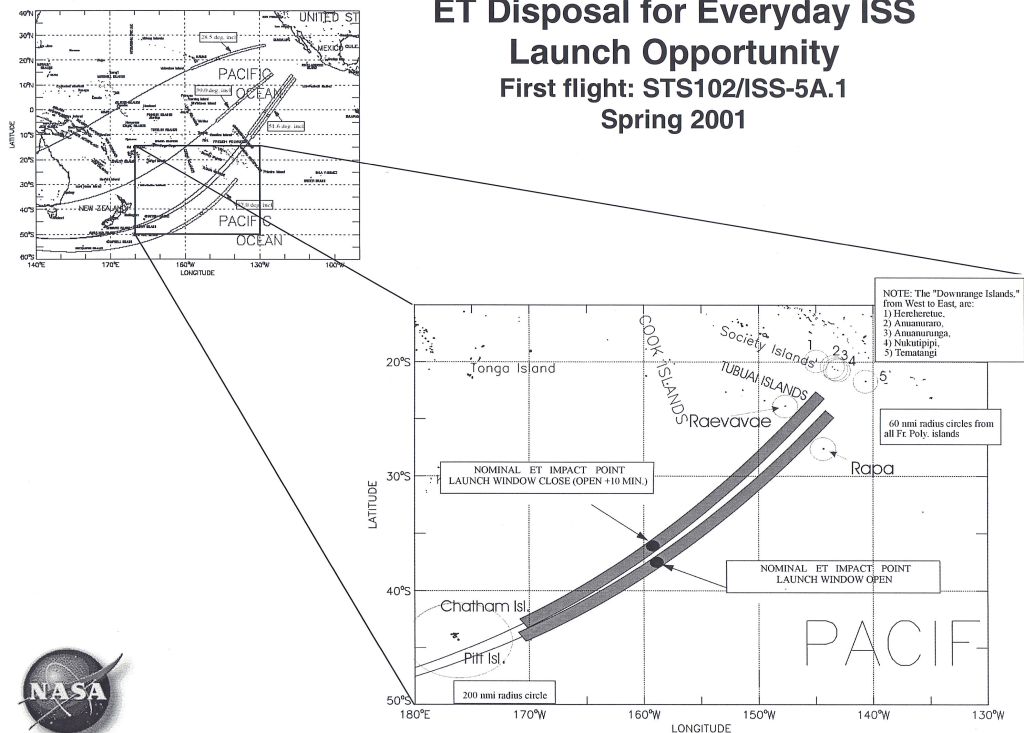

Getting ready to assemble the ISS, it was important to maximize the launch window and one way to allow more launch opportunities was to lower the insertion orbit. In the arcane world of orbital rendezvous, coming in lower allowed more opportunities to launch. Take my word for it – maybe another blog post for another day – it works. So, the trajectory analysts looked to insert – which is to say, cut off the Main Engines – when the apogee of the orbit was 122 n. mi. – down from the previous target of 173 n. mi.

This caused the ET disposal footprint to move from the Central Eastern Pacific – east of French Polynesia and west of Mexico – to a location farther south and west, between New Zealand on the west and French Polynesia on the east. And unfortunately, the end of the ET disposal footprint extended into French Polynesia.

Here it might be useful to be familiar with the islands of the South Pacific . . . which I was not. (Maybe I need to read Michener’s ‘Tales of the South Pacific’).

Close to the west end of the footprint (the ‘heel’), Pitt Island (New Zealand, population 38), the Bounty Islands (New Zealand, uninhabited bird sanctuary), and Auckland Islands (New Zealand, uninhabited) were close to the footprint but protected. That is to say, the 3-sigma debris footprint was outside 200 n. mi. from their beaches.

On the east end of the footprint (the ‘toe’), the French Polynesian islands of Tematangi (population 58), Hereheretue (population 56), Anuanuraro (uninhabited), Anuanurunga (uninhabited), and Nakutipipi (uninhabited most of the year) were also similarly protected. (Note: spelling may vary).

But I imagine those 100 or so people got quite a light show on occasions!

Several of these islands were considered bird sanctuaries which, we were told, were periodically visited by scientists conducted bird population surveys. We never knew when people might be there.

But we had one real infringement problem. Two French Polynesian Islands were just inside the footprint: Raivavae (population 900) and Rapa Iti (population 500); left and right of the ground track respectively. Our 3-sigma footprint – in the sideways or ‘crosstrack’ direction – came just outside 60 n. mi. from those two islands. This violated the 200 n. mi. limit that we were obliged to protect. None of our trajectory tricks worked, we were stuck with a violation or loss of possible launch days.

The analysts calculated that the possibility of an ET fragment – in the crosstrack direction – exceeding 3 sigma dispersion (27.5 n. mi.) by the additional 60 n. mi. was less than 1 x 10-10 probability. One chance in a very large number. You have better odds at the lottery. And remember, we only protected US beaches by 25 n. mi., 40% less distance.

In one of their rare helpful instances, NASA HQ talked to the Department of State about the situation. State encouraged us to write a letter asking permission to come within 60 n. mi. of these two islands rather than the standard 200. Under their tutelage, we drafted a very nice letter asking permission of the French government for this exception. The letter – a formal diplomatic note – was sent in December of 1998. Copies of the letter were sent to the South Pacific Forum and the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme. In the next year, NASA sent teams to visit Tahiti to explain the situation and also presented a summary to the New Zealand embassy in Washington.

And we waited for a response from the French.

Which never came.

After a year with no response, the State Department effectively told us that the French had been adequately notified and receiving no objection, we could put the plan into operation.

So, we did.

I wonder if French ESA astronauts Leopold Eyharts (on STS-122) or Philippe Perrin (on STS-111) directly benefited from the increased launch window. I will have to research that.

If you think this is complicated, next consider off-nominal – underspeed and abort – cases where we also had to protect for safe ET disposal.

I never heard a report of any sightings or objections from folks in the South Pacific. Or the French government.

Except one story. For another day.

I always wondered about the ET destruction events and never knew some were captured on video. And when you say the tanks would “break up”, the video clearly documents break up was a violent and instantaneous event!

As always, I appreciate your explanation of a very complex topic with a multitude of variables, Wayne. For those who aren’t convinced schools should teach Algebra II and higher, math and probability/statistics are absolutely critical as they are integral to navigating our world–sometimes a matter of life or death…and even preservation of unique bird species!

Great post. It clearly shows how NASA is an environmental agency as well as a space agency. That’s mandated in the agency’s Organic Act, but this is a good example of how much care went into that mandate. Since I worked as a National Park Service Ranger before joining NASA Education, the post speaks to me.

Watching our X-friend launch without a flame trench makes me wonder how he would handle such a situation.

I have the Pat Rawlings original painting of a stack of ET’s being cut up and fed into a beam builder co orbiting with Space Station Freedom.